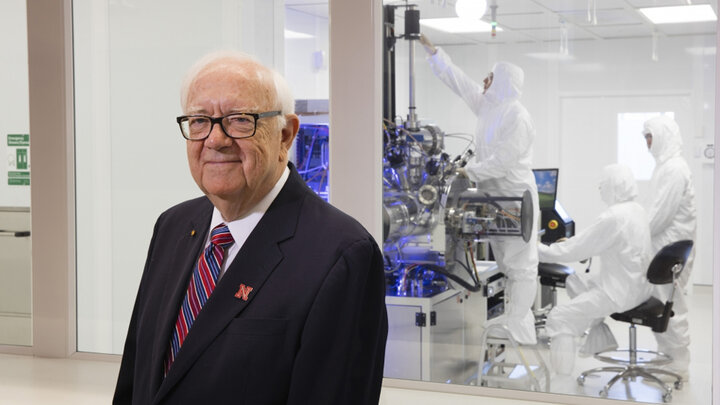

Much has been written about David Sellmyer’s 47-year career as an outstanding materials and nanoscientist researcher at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. His work to establish multiple research centers has permanently altered the trajectory of research at Nebraska for the foreseeable future.

These include the Center for Materials Research and Analysis in 1988; the National Science Foundation-funded Materials Research Science and Engineering Center in 2002; the W.M. Keck Research Center for Mesospin and Quantum Information Systems in 2002; the Nebraska Center for Materials and Nanoscience in 2006; and the NSF-funded Nebraska Nanoscale Facility in 2015.

Under his leadership, the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences increased its sponsored external research funding from $2.7 million in fiscal year 1998 to $13.6 million in FY 19 — a more than 400% increase.

Beyond his accomplishments that can be quantified, those who work closely with Sellmyer, George Holmes University Distinguished Professor of physics and astronomy, talk about his qualities that are harder to quantify. When asked about Sellmyer, colleagues ranging from past students, fellow researchers and administrators, and administrative coordinators highlight the qualities that elevated him from a top-notch scientist to a leading research leader and mentor: his ability to inspire, his decent treatment of all people and his knack for seeing the big picture.

Rebecca Richards-Kortum, a past student of his in the early 1980s, called it “his superpower” in her commencement speech last year to Nebraska graduates. She is now a professor of bioengineering at Rice University and director of the Rice 360 Institute for Global Health.

As a sophomore, Richards-Kortum was a physics major considering a move to mechanical engineering. She’d met with the associate dean of engineering, who said he noticed that women found the engineering curriculum very challenging. When she met with the physics chair, Sellmyer took a different approach.

“He asked me if I liked physics, and when I said I did, he told me, ‘Don’t switch majors.’ In fact, he said, ‘You should come and do research in my lab.’ So, for two years, I worked in Dave Sellmyer’s lab and it changed my life. His superpower is believing in people.”

Richards-Kortum attained a master’s and doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and has researched low-cost methods to end preventable infant death in Africa and affordable methods for detecting cancer and infectious diseases in her Optical Spectroscopy and Imaging Lab at Rice. She’s had a role in developing 40 patents and recently was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” in 2016. Richards-Kortum also spearheaded a team that was a finalist in the MacArthur Foundation’s inaugural 100&Change competition. Her success reflects Sellmyer’s talent for helping others reach their potential and highlights the power of great leadership.

Sellmyer’s contributions in quantum and spin phenomena in nanomagnetic structures were themselves remarkable — he didn’t need to add the extensive administrative and fundraising work of developing and leading research centers. What made a man so interested in minuscule particles turn his attention to the “big picture?”

Nebraska’s Dan Claes, professor and chair of physics and astronomy, said Sellmyer developed this larger vision for the department soon after coming to Nebraska from MIT. He saw that a number of prominent physics faculty, hired at Nebraska in the 1960s with NSF funding following the Sputnik launch, would soon retire, and the department couldn’t replace all of them. To fill the void, he developed a new strategy.

“Funding agencies were starting to recognize the value of collaborating faculty — that it would be a multiplier effect where you’d get more bang for your buck,” Claes said. “If enough of the people in physics were willing to pivot a little bit in order to link together their proposals, they could put together joint proposals to go after the larger money.”

Sellmyer identified signature core areas in the department: atomic physics, solid state and astronomy being clear examples. When hiring opportunities arose, the departments would bring on experts in those core areas.

“Dave first articulated what came to be the guiding light for the department by developing a long-term strategy that we’re still following today. We now just focus on condensed matter, solid state, atomic and high energy, but that’s been the secret to our strength,” Claes said.

Sellmyer is that rare combination of outstanding scientist and leader. Though he estimates he’s spent about two-thirds of his career helping others collaborate, he never turned away from his own research.

“You cannot be a successful administrator or department chair if you’re not highly active in your research,” he said. “I tried to maintain that activity in research all the way through. That meant delegating responsibility to committee chairs and not micromanaging.”

Key to Sellmyer’s success was aligning three critical elements he identified as crucial to materials and nanoscience research at Nebraska: talent, infrastructure and funding. He credited the chairs he’s served under, deans, associate deans, vice chancellors for research, and others for providing him support and resources.

Sellmyer credited his administrative coordinator, Shelli Krupicka, for “keeping the whole ship running.” Sellmyer was Krupicka’s first boss at Nebraska when she started in 1990 and she remained his assistant until October 2019. She now assists NCNM interim director Christian Binek.

During their 30 years working together, Krupicka saw Sellmyer’s leadership transform materials research and nanoscience. Eventually, it landed her in a brand new building, the Nanoscience Research Center, which provides centralized research core facility space available to dozens of physics, chemistry, engineering and other faculty members.

She attributed Sellmyer’s leadership success to his manner of treating people: “Dr. Sellmyer is very good at getting people to work together toward a common goal, and he is always positive. He is a great listener and he just brought out the best in people.”

As he nears his retirement, Sellmyer is happy to see ORED launch the Research Leaders Program. While he enjoyed broad support from the university administration over the years, he sees the benefit of helping faculty at an early point in their careers develop tools to marshal the talent, infrastructure and funding needed to launch new research centers.

He encouraged researchers to take a step back from their science and look at the bigger picture to find opportunities to diversify and collaborate with colleagues to solve bigger, more interdisciplinary problems.

“Leadership has so much to do with willingness to act. If you just do the hard work of organizing and calling meetings and getting people together, you end up being a leader,” Sellmyer said. “Be a bit selfless, be about people, love your work, and I think good things will happen.”